Conditioned to Stay

The Neuroscience of Abusive Relationships

Hi again!

I have crawled out of the depths of hell (long COVID) to temporarily rejoin society before retreating again.

Picking up where I left off - I have been resharing some of my writings from last year. These are pieces that were published as a spotlight had finally been shined upon my abuser, John Romaniello (if you’d like more information, you can browse my previous publications).

If you have never been in an abusive relationship (or perhaps you are now out of one yourself), it’s often hard to look at these harmful relationships and understand why people stay (or maybe even why your past self had stayed).

I mean, if I had a penny for every time I knew I got treated like a piece of shit and still came back practically begging to continue to be treated as garbage, I’d be rich-rich.

There are many different paradigms and considerations in beginning to unravel these relationships and power dynamics, but one that I haven’t often seen addressed is some of the neurological and psychological bases for being trapped in the cycle of abuse.

This writing is an exploration of some of those concepts in an effort to understand how abusers take power in relationships and perpetrate a cycle of dependence and conditioning.

If you haven’t read some of my previous writings, I would recommend doing so if you’d like some more context. This does work as a standalone piece, however. I’ll warn you, it’s quite long and could definitely be broken up into multiple pieces, but my long covid ridden brain doesn’t have the bandwidth for that today, so I’ll leave it to you.

I know for the most part, the online shenanigans have blown over. But I still feel some sort of calling to write about it. For those of you who have stuck around this long and have supported me - sincerely, thank you.

So much healing and catharsis has come from being able to share with you. While I don’t believe our traumas must always be a tool or a lesson, sharing with you all has allowed me to assign some personal meaning to some of the worst years of my life. Truly - if my story makes one person feel less alone or helps someone become a more compassionate ally - that’s more than enough for me.

Nobody Asked Me,

D

I’ll never paywall anything I believe is important, educational, or meant to help others. Paid subscriptions are simply a generous way to keep this work going.

Once upon a time, a little bit longer ago than I care to admit, I was in a lab studying PTSD in the brain.

For those of you who are new here, my degree is actually in neuroscience. 🧠

My honors thesis and research was in PTSD (specifically contextual cue learning).

So, today I kind of wanted to switch gears to talking about some of the neuropsychology behind abusive relationships.

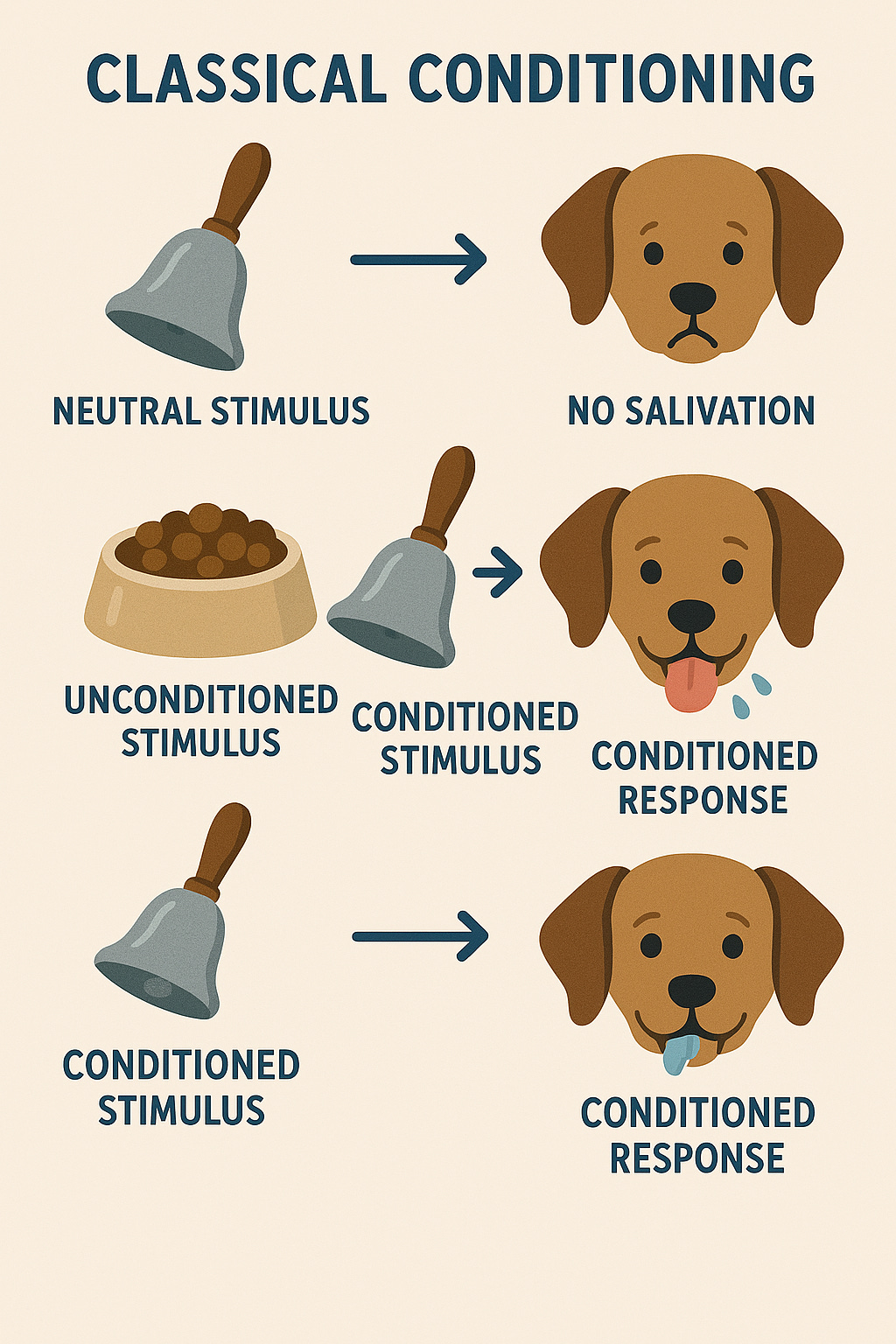

There are two foundational theories of learning in psychology. If you’ve taken an intro to psych class you probably remember: classical conditioning and operant conditioning.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning has notoriety through Pavlov’s dogs.

In classical conditioning, you’re dealing with learning through association.

This method of learning was discovered when one day a man named Pavlov was feeding his dogs. After many meals of feeding his dogs, at this one dinner, he noticed something. It dawned upon him that when he rang the bell signaling dinner, the dogs started to drool as if they were already presented with food.

He uncovered that dogs could associate a neutral stimulus like a bell, with an unconditioned stimulus (a stimulus that results in an automatic and unlearned response), in this case food.

Over time, dogs would start to salivate with just the bell. The salivation from food is the unconditioned response.

Eventually, salivation over just the bell would be the conditioned response.

So, basically he’s proving we are no better than dogs when we hear that door dash ping.

Operant Conditioning

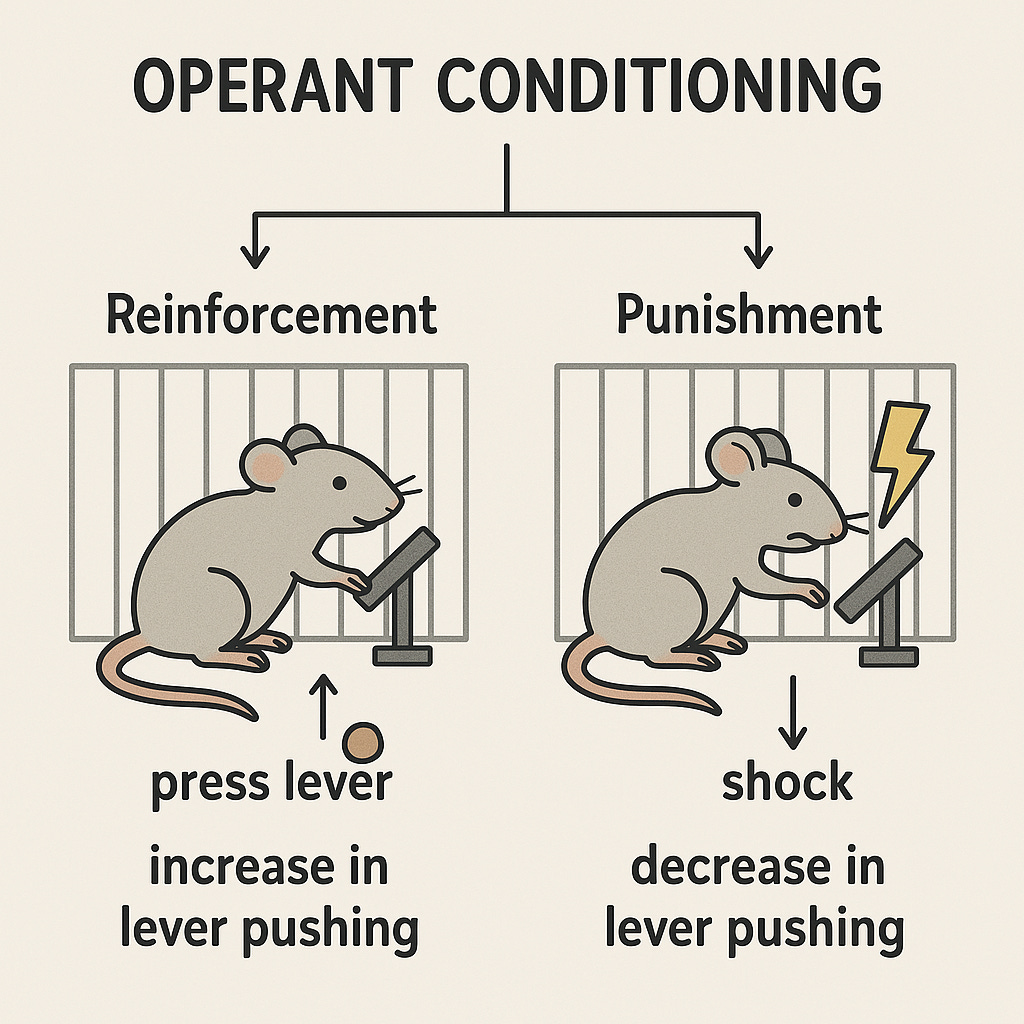

The second form of learning, operant conditioning, focuses on consequences.

In operant learning, behavior is shaped and maintained through consequences.

Good consequences, called reinforcements, increase the wanted behavior.

Bad consequences, called punishments, decreased the behavior.

While we won’t be referencing it much, both consequences and reinforcements can be positive or negative - this doesn’t measure the desirability of a the stimulus, rather if you are adding or removing something e.g. negative reinforcement is getting rid of something aversive or positive punishment is adding an aversive stimulus.

So you have a little rat in a cage. There’s a lever in the cage. He spends time wandering around, eventually gets curious and presses the lever - lo and behold, a little treat comes out! He might wait some time and then press it again - wallah! More treats. Here, the rat is learning through the positive reinforcement of the treats to push the lever.

On the flip side, perhaps another rat is wandering a different cage. He gets bored and flips the lever. He gets shocked - this is a punishment. This will discourage the rats from pressing the lever.

Now, there are a few different characteristics of operant learning, but the bits that are interesting to us have to do with how the rewards are given. There are two types of schedules - ratio and interval.

Fixed interval schedule happens at a fixed amount of time after the response.

Ex. You get paid every two weeks if you work.

Variable interval schedule is when the reinforcement happens at a varied amount of time after the response.

Ex. Checking emails

Fixed ratio schedule occurs after a fixed number of responses have been emitted since previous reinforcement.

Ex. Think a free coffee after 10 punches.

Variable ratio schedule is when reinforcement occurs after a variable number of responses.

Ex. Slot machines or why we continuously update Instagram hoping for some new interesting dopamine hit.

Continuous reinforcement is when reinforcement occurs after every response.

Ex. Every time the lever is pressed, a treat is dispensed (we love a little treat!)

Variable ratio is the most addictive schedule - it’s what social media and casino slots have in common. Gamblers don’t know when their next win will be, but they’ll keep trying hoping the next one will be a win. The random reinforcement encourages frequent repeated amounts of the behavior.

Okay SO. Let’s take this back to the context of abusive relationships.

Classical Conditioning in Abuse

First, let’s revisit the classical conditioning model.

Classical conditioning is the model most frequently used to explain fear.

Since classical conditioning focuses on automatic, involuntary responses - it is similar to fear. Fear often bypasses conscious thought and works on automatic responses such as increased heart rate, sweating, freezing, etc.

💡 In fact, this is a learning model used in studying PTSD. Think about it.

For example, if a loud sound, (unconditioned stimulus) naturally invokes fear (unconditioned response), pairing that sound with a neutral stimulus (like a location), can cause the location alone to evoke fear (conditioned response).

Say you got yelled at a lot in a certain bedroom. Revisiting the bedroom, which was completely neutral, could trigger a fear response in someone with PTSD.

In fact, this model of learning explains why PTSD is such a challenging disease to treat - there are infinite amounts of context cues that our brain is subconsciously processing - smells, colors, voice intonations, sounds, time and space, it’s practically infinite. So, imagine how hard it would be to try an attempt to de-escalate fear responses for each of these triggers.

It’s not easy.

That’s classical conditioning.

Like what I talked about earlier, neutral stimuli can start to illicit a fear response, like what we see in PTSD.

So for example, if after your abuser says “we need to talk” right before he yells at you for hours - the phrase “we need to talk” can evoke fear alone.

We usually think of conditioning in terms of fear, but abusers also exploit the other side of the equation: attachment. After an explosion of abuse, they often intersperse kindness—the “honeymoon phase.” An apology, a gift, or simple affection (the unconditioned stimulus) brings relief and feelings of love and safety (the unconditioned response).

Over time, the abuser’s presence—or even just words like “I’m sorry”—becomes enough to trigger those feelings of closeness (the conditioned response), regardless of whether their behavior has changed. This helps explain why many victims feel warmth or longing for their abusers, even while recognizing the harm. They’ve been trained to associate comfort with the very person causing pain.

What makes this so sticky is the order: in most abusive relationships, the positive conditioning happens first. Early in the relationship, the abuser is attentive, generous, affectionate. The fear comes later. So the victim’s brain learns to associate the abuser with safety and love long before it associates them with harm.

And unlike deleting a file from a computer, conditioning doesn’t simply “unlearn.” Old pathways remain in the brain; new, healthier ones must be built on top of them. That’s why no contact can feel so brutal—the brain craves the familiar, conditioned pathway, even if it’s toxic. Relapse into longing isn’t weakness, its a physiologically conditioned response.

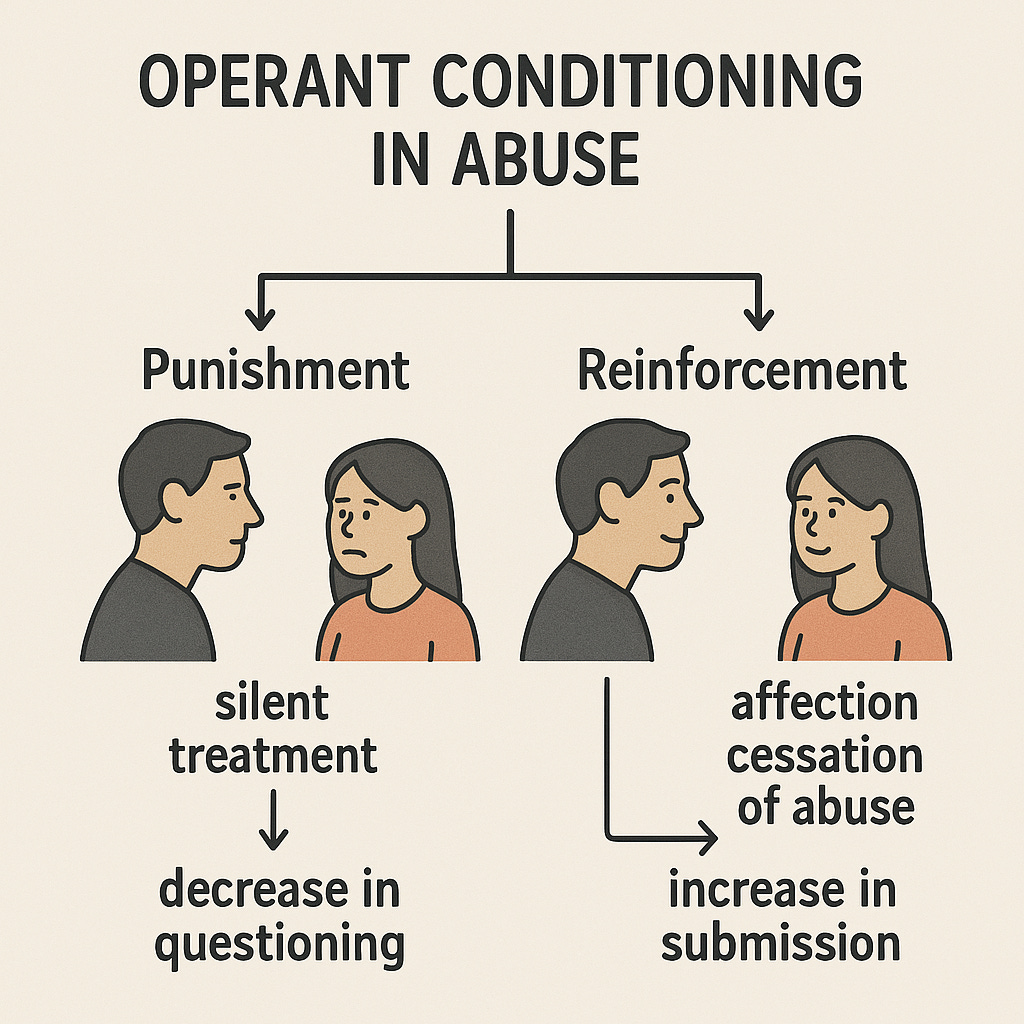

Operant Conditioning in Abuse

This model, I feel is more strongly tied to actual abusive behaviors in a relationship.

Remember, operant conditioning has everything to do with consequences. Consequences are reinforced or punished to direct the behavior patterns.

So, for example, abusers may use emotional punishment to suppress behaviors they don’t like (like questioning, asserting dominance, or leaving the relationship). Ever heard of the silent treatment? This sort of behavior discourages the victim from whatever behavior the abuser no longer wants to see.

Ex. Victim stands up for themselves, abuser punishes them by not talking to them. The victim learns to not stand up for themselves because the consequence is unpleasant.

Or, abusers will reinforce submission with rewards through temporary affection or cessation of abuse. This teaches the victim to comply with the abusers demands.

Ex. When the victim is tip toeing around their abuser, making sure they are doing everything the abuser wants, the abuser might give the breadcrumbs of affirmation or signs of love that the victim so desperately craves. The victim is reinforced the the consequences of behaving as the abuser has groomed you to be, gives benefits.

If you think about the cycle of abuse - after the tension building and the explosion, comes the honeymoon phase. The honeymoon phase is reinforcement and encourages the victim to stay (the wanted behavior).

Now, take it a step further with the scheduling of these reinforcements or punishments. In most abusive relationships, when you get the reward is unpredictable - same goes for punishment. That random and unpredictable reinforcement schedule is the most addictive sort of operant learning.

This is a pattern seen in abusive relationships and toxic cycles - the honeymoon phases and outbursts happen randomly. This quite literally makes the relationship more addictive.

In other words: you’re not crazy for missing someone who treated you like garbage. Your brain got tricked into thinking crumbs were a whole damn meal.

And last notable parallel is, operant behavior explains learned helplessness.

Learned helplessness is defined in behavioral sciences, as the failure to escape shock induced by uncontrollable aversive events.

In 1967, there were two scientists that theorized that animals learned that outcomes were independent of their responses - that nothing they did mattered - and that this learning undermined trying to escape.

If a victim has tried a behavior too many times (like asking for something or setting a boundary) and it has been met with punishment, that behavior will slowly start to diminish.

When someone tries to change their situations repeatedly to no avail, the brain will conserve itself and shut down.

Abusers are great at creating situations where leaving feels impossible and the victim feels trapped - and oftentimes, there are many factors limiting and trapping the victims.

Learned helplessness doesn’t have anything to do with the willpower of the victims. It is the psychological and neurological state that is developed after periods of prolonged stress or trauma.

With help and healing, the victim can learn to develop sense of agency again.

So that’s all I have for you today.

I hope perhaps this gave a new way of conceptualizing some key aspects of abusive relationships and it ultimately helps you understand more about these dynamics.

I think one of the biggest challenges we currently have in making progress/advocacy for survivors is a lack of understanding. Whether that’s not understanding what an abusive relationship is, what it looks like, or why people stay - understanding is a gateway to compassion.

Nobody Asked,

Dimyana